Self Actualization in the Kitchen of Yesterday

Is the ideal kitchen just...any kitchen where you get to do whatever you want?

The Kitchen of Tomorrow—and the Miracle Kitchen, and the Kitchen of the Future—had a great run. For a few decades in the middle of the 20th century, high-tech dream kitchens conjured up by leading appliance manufactures were the centerpieces of extravagant short films, drew curious visitors at General Motors Motorama, traveled to Moscow in the service of their country, and inspired movies and TV shows with gadgets that promised to prepare food and clean up while you read a magazine. Or, if you were Doris Day in Glass Bottom Boat, you watched in horror as your expected role in life was erased from existence by a machine.

Kitchens of Tomorrow weren’t realistic; they were like concept cars, meant to inspire and dazzle, in some cases like the fantastical Miracle Kitchen, designed @ the Soviet Union to present American middle class life through rose colored glasses and intimidate our adversaries. And they offered American women a curious bargain: eschew work and professional advancement, and we’ll help make housework easy for you. That is, the main thing you’re supposed to do. Just do less of it. That way you can volunteer, take classes, spend time with your kids, host parties, take up golf or tennis, and perhaps even help defeat the Equal Rights Amendment in your discretionary time.

What’s fascinating about the kitchen culture of the 1970s—which is when American women began working outside the home in significant numbers for the first time since World War II—is that for some, the association between modern appliances and the space race began to lose some of its campy luster. The monotonous convenience of it all was rather bland, and the wood-paneled kitchen of yesterday was thus enchanted anew by foodies and the homestead-curious. Manufacturers and advertisers got in on the trend right away: natural materials, earth tones and hanging plants were in, turquoise, chrome, and aerodynamics were out. Even Betty Friedan weighed in on how much she enjoyed making soup in the New York Times in 1977.

Last week I had the singular pleasure of talking to my pal Sarah Marshall about the woman who exemplified this cultural shift at its most appetizing and chic: Martha Stewart. You can hear our conversation on this week’s episode of You’re Wrong About. I’ve admired Martha with perplexed fascination for decades, but I hadn’t thought much about her early years much until recently, and I’m struck in looking through her landmark first book Entertaining, or the 1977 Better Homes and Gardens spread about Turkey Hill (her iconic Westport, CT home) how much of a back-to-the-land figure she was then. Bucolic scenes show Martha tending her vegetable garden, arranging flowers, and gathering eggs from her own chickens.

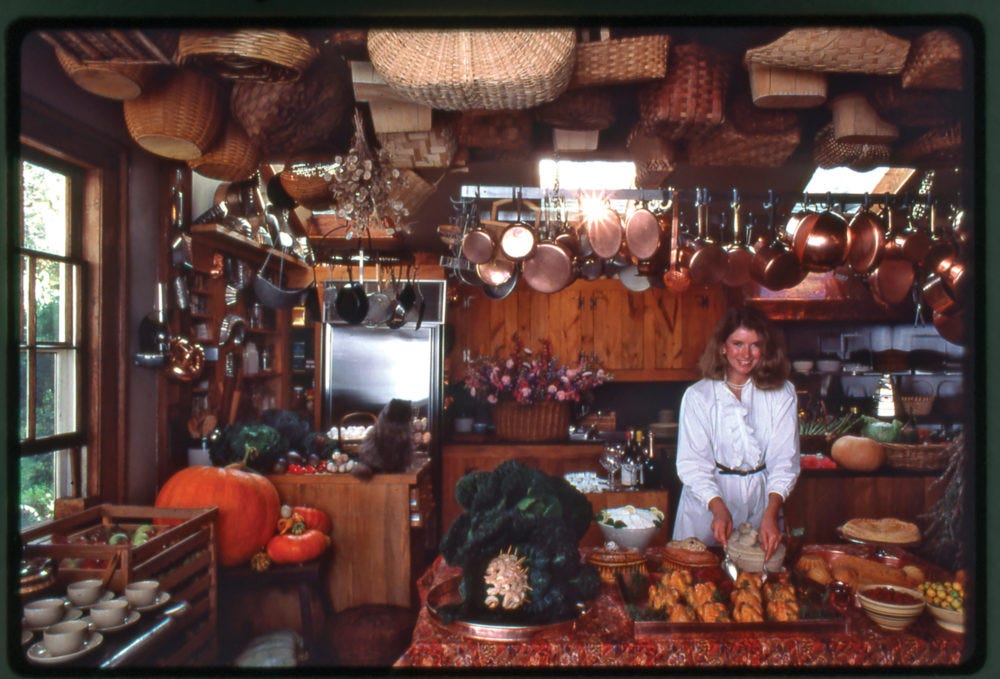

Circa “Entertaining” (1982) Martha’s kitchen was stuffed to the gills with copper pots and woven baskets. There is some gadgetry, like the ivory-colored Cuisinart identical to the one I remember from childhood, but the few bits of modern technology are visually overpowered by forces of nature: flowers, food, wooden cabinets, and the glowing visage of Martha herself, dressed in a white cotton dress, sporting minimal makeup and smiling. In 1982, perhaps not coincidentally, “Little House on the Prairie” was still airing on NBC.

Martha’s calling card—not always happily received—has always been her drive to initiate American women into the mysteries of DIY. She has taught readers and viewers to rewire vintage lamps, paint their own floors and porches, and make homemade versions of Dove Bars. She has shared endless iterations of hand-calligraphed place cards and Valentines, and evinced her love of America’s favorite holiday by promoting a distinctive brand of spooky-posh Halloween decor. In a country where convenience and technology are celebrated for having liberated women and won the Cold War, this is both a curiously retrograde and anti-corporate stance for a woman who is quite literally synonymous with her own corporation.

Making things from scratch is one of those activities that finds strange bedfellows across the political spectrum; it simultaneously short-circuits our reliance on corporations to produce what we need, and locks women into intensely time-consuming projects, diverting their attention and energy away from activities beyond the domestic sphere. It’s fraught. I think one of the primary reasons Martha inspired such intense feelings at the zenith of her empire in the 1990s was that her endeavors worry our unsolved domestic conundrum like a loose tooth. We don’t have universal childcare or paid leave, we can’t seem fix it, we live in a status-obsessed society where every tasteful detail counts, domestic work is hard and unequally divided, everyone is tired, and Martha was ever present to remind us of what we could be doing.

But what if “what we could be doing” is just…what we want? Martha’s TV show and late, great magazine presented her as a capable woman in charge of a great estate where various workers, pets, and farm animals were busy checking off their to-do lists while Martha embarked on projects redolent of creativity and domestic splendor. You never doubted she could clean a bathtub, but her show really offered you the fun stuff: pet grooming, sculptural sugary confections, collecting FireKing Jadeite, learning about indigo dyeing, and browsing paint colors from a palette that looked as though it had been smuggled out of a Federal-style parlor in a time machine. Obligatory nods to husbands and children were present, but you could just tell that Martha was happiest overseeing her beehive in the company of critters and various skilled craftsmen. This vision of domesticity is both deeply traditional and quite radical: it’s joyful housework for personal enjoyment, not for servitude.

Postwar kitchens really did change women’s lives drastically. The feeling of it all being a kind of “miracle” is due in part to the fact that the municipal services that made modern kitchens work (running water, gas, electricity) revolutionized daily life—not just the kitchen per se, but the whole world. By contrast, the women’s liberation movement in the 1960s and ‘70s brought women into professional and civic life in record numbers, but didn’t do much to change the balance of labor at home. By the 1980s, it almost didn’t matter that appliances were increasingly a sad, off-white almond color because no appliance, piece of technology, or wipe-clean countertop can fix what ails American women, which is a crushing combination of domestic and professional responsibilities that has remained stubbornly in place despite six decades of social progress. I have a suspicion that this partly explains why the kitchens of the 1970s and ‘80s were so conspicuously homespun: if you’re not there most of the day—and perhaps you feel uneasy about this—when you come home and cook, you want to really make it count. Putting a lace valence on the whole operation sends a powerful visual message.

I don’t think perfection is really what was annoyed Martha’s most critical viewers. Her existence, at least on TV and in her magazine, seemed to involve doing the elaborate projects that she liked, and no others. There’s an implicit, invisible support system (in her case, wealth and staff) that shows viewers what domestic life could perhaps be like if we weren’t run so ragged. It could be slow, abundant, creative, fun, frivolous, entrepreneurial if we like, or totally inefficient if we like that better. Consider: perhaps it’s not Martha you hate, and it’s not your kitchen, it’s the social inequality and relentless grind that makes the sort of domestic pleasure Martha celebrates so unattainable. The challenges American women face urgently call for policy solutions. Inequality may be “by design” in the grand sense of the word, but in and of itself, domestic inequality is not a design problem.